Hidden Treasures in Museum Drawers

Lessons from Enigmacursor

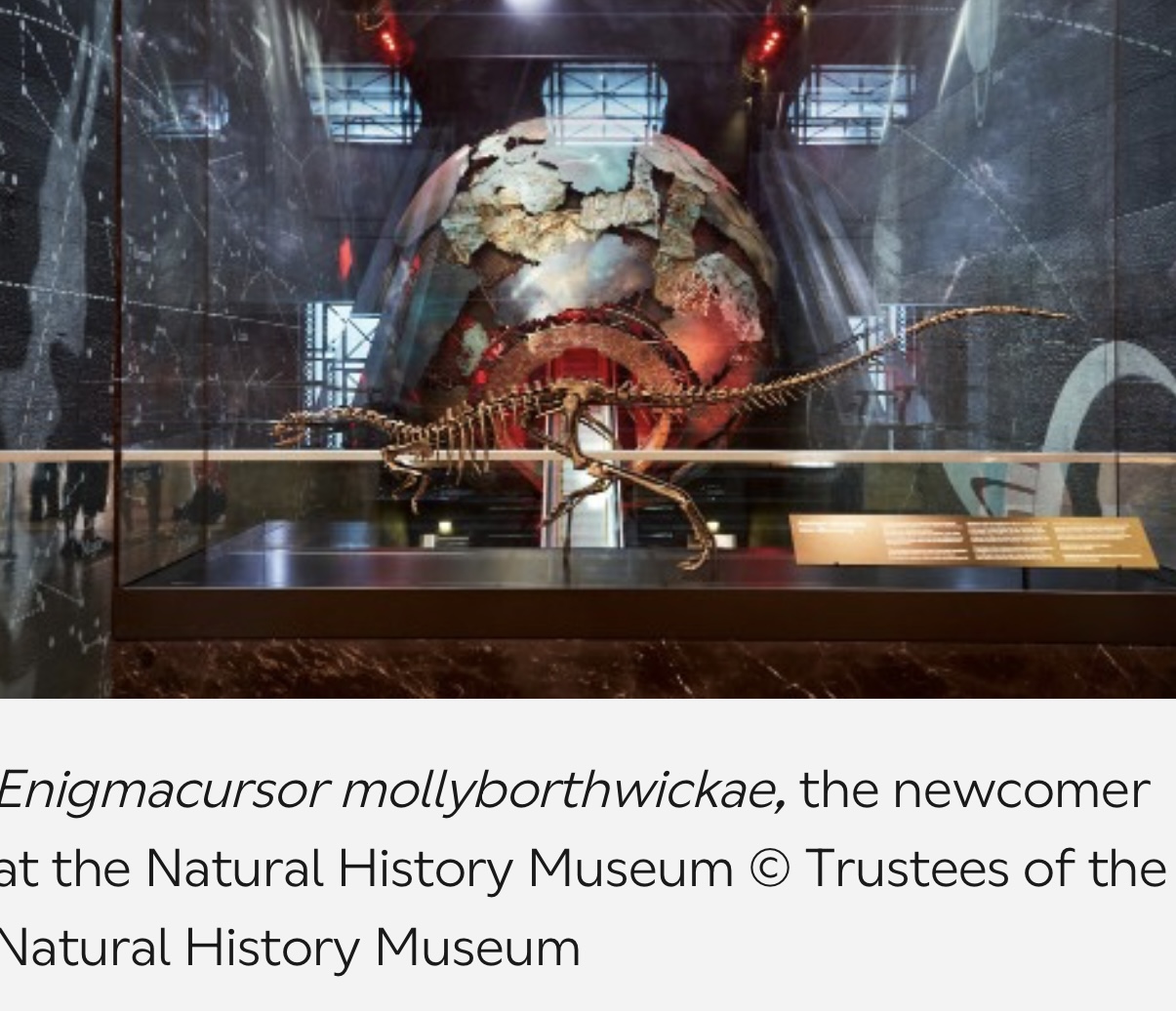

The story of Enigmacursor mollyborthwickae is not just about a new species; it’s about the power of collections. The fossil had sat in a museum drawer for decades, labelled as part of the genus Nanosaurus. Only when palaeontologists revisited the specimen with fresh eyes and comparative techniques did they realise it represented something unique. This tale is not uncommon: museums around the world house millions of fossils, many of which have never been studied in detail.

Re‑examining old specimens can lead to surprising discoveries. Advances in CT scanning allow researchers to peer inside bones without damaging them, revealing growth rings, internal cavities and muscle attachment sites. Digital modelling lets scientists reconstruct missing parts and test how ancient animals moved. By combining these methods with careful comparisons, researchers identified Enigmacursor as a fast‑running ornithischian distinct from Nanosaurus. The case underscores why preserving and cataloguing fossils is as important as finding new ones.

Museum collections also provide context. By comparing Enigmacursor with other Morrison Formation dinosaurs, scientists can infer how small herbivores coexisted with giants like Diplodocus and predators like Allosaurus. Such comparisons reveal patterns of diversity, growth and extinction across time. They also allow researchers to revisit earlier hypotheses: bones assigned to one species may turn out to belong to several, while isolated bones may finally find a home in a new skeleton. The lesson is clear: in palaeontology, there is always more to discover, even in the most familiar drawers.

Credit: Kumiko / Wikimedia Commons

Sources: Sci.News coverage of Enigmacursor and the Royal Society Open Science paper.