Ankylosaurs Take Experimentation to Extremes

Revisiting SpicomelluS

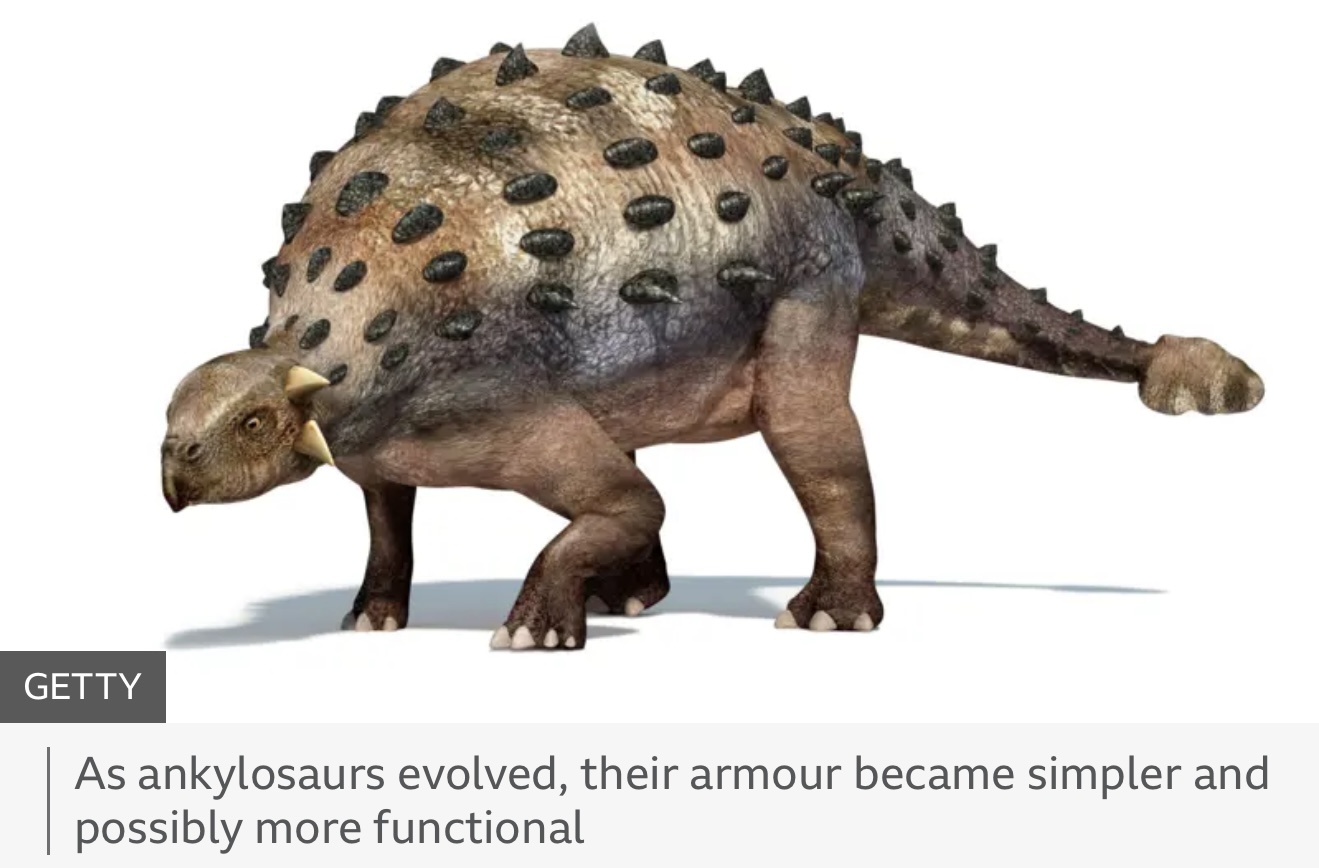

We’ve already met Spicomellus afer, the Moroccan ankylosaur with a collar of metre‑long spikes. But what do those spikes really tell us about the early evolution of armour? New research delves into the function of Spicomellus’s unusual defences and what they reveal about ankylosaur experiments. Each spike is fused directly to a rib, unlike the detachable osteoderms of later ankylosaurs. This arrangement would have stiffened the animal’s torso and made it difficult for predators to bite into the neck and shoulders.

Biologists note that such extreme armour comes at a cost. Heavy spikes reduce agility and increase the energy needed to move. In Spicomellus’s case, the trade‑off may have been worthwhile: predators of the Middle Jurassic included formidable theropods, and few other herbivores had comparable armour. Spicomellus may also have used its spikes for display. In many modern animals, such as horned lizards and porcupines, elaborate armaments serve to deter predators and attract mates. The fusion of spine and rib might have created a rigid platform that supported keratin sheaths or skin flaps, making Spicomellus even more striking.

The species also hints at an arms race within ankylosaurs. Over the next 30 million years, the group experimented with different arrangements of armour: some evolved overlapping plates, while others developed massive tail clubs. By the Late Cretaceous, ankylosaurs were walking fortresses, but Spicomellus shows that their evolutionary story began with radical and sometimes awkward innovations. Studying such early experiments helps palaeontologists understand how natural selection shapes body plans and how lineages explore and discard various strategies before settling on successful designs.

Credit: Kumiko / Wikimedia Commons